As a tropical storm battered parts of Texas with more than 40 inches of rain in 72 hours last week, Congress is debating whether to extend the National Flood Insurance Program, which expires on September 30. The NFIP is a government-run flood insurance plan that covers 5 million policies and is an alternative to the relatively shallow private flood insurance market. Since the passage of the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, Congress has often waited until the last minute to reauthorized the program before its expiration and passed only short-term extensions (12 since 2017).

Last week, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a continuing resolution to keep the federal government funded through November 21 and prevent a government shutdown. This measure included an extension for the NFIP through the same date. But it is unclear whether the Senate will pass the resolution or allow a shutdown.

The House of Representatives Financial Services Committee unanimously passed a bill titled the National Flood Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 3167), which would reauthorize the NFIP for five years and provide funding for flood mapping and flood mitigation programs. It would also mandate a number of reforms, including allowing policyholders to get refunds if they cancel their policy before its expiration date, eliminating penalties if insureds leave the NFIP for the private market, and requiring the NFIP to increase premium rates each year.

On the Senate side, there is a bill of the same name that would also extend the NFIP for five years. The bills would also cap annual rate increases at 9% (as opposed to the current law, which allows increases by up to 25% annually), making the program more affordable, especially for low-income policyholders. Additionally, it includes provisions to protect homebuyers and renters by mandating flood risk and prior flood damage disclosures, and also funds flood mapping modernization and mitigation. As of this writing, the Senate has not voted on the measure.

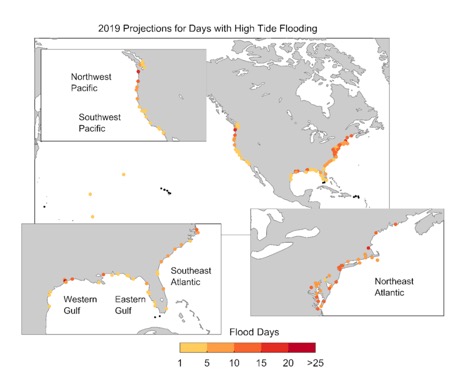

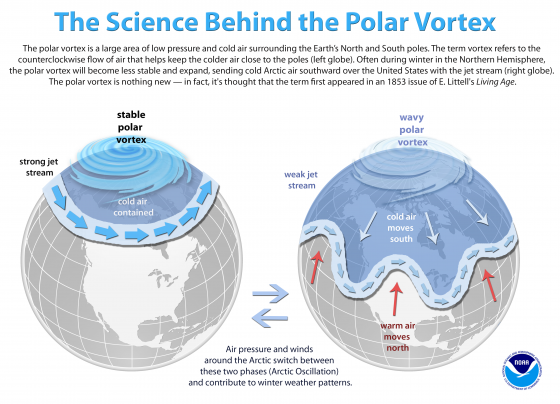

Climate change has exacerbated annual flooding across the United States, making storms more violent, frequent and costly. In its June report on the flood outlook for 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration noted that non-storm, high-tide flooding “is increasingly common due to years of relative sea level increases. It no longer takes a storm or a hurricane to cause flooding in many coastal areas.” And in May, NASA said that the United States had experienced record-setting precipitation, characterizing it as the “soggiest 12 months in 124 years of modern record-keeping.”

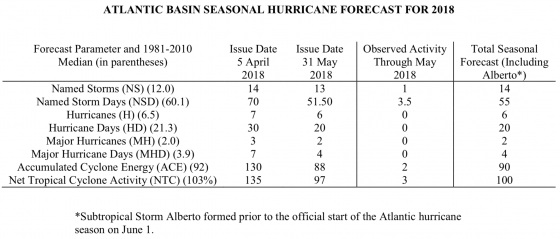

They also mean millions more in property damage, which in turn means more people getting payouts from the NFIP. In fact, the series of hurricanes that hit the United States in 2017 and 2018 also hit the NFIP hard—the program lost billions of dollars in payouts, leading the government to pass a disaster relief bill that helped the NFIP pay the claims. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which runs the NFIP, aims to double the number of people who have flood insurance by 2023, but according to E&E News analysis, coverage in the United States has declined by 31% since 2011, leaving many without protection if they are hit with flooding.

In 2012, Congress passed a law allowing federal agencies to begin accepting private flood policies, but the market has been sluggish to fill the gaps. Some are stepping in—indeed, the American Association of Insurance Services (AAIS) today announced a partnership with Munich Reinsurance America, Inc. (Munch Re) to provide flood insurance aimed at homeowners outside major flood zones. But with few other private insurance companies offering flood policies, if the NFIP is not reauthorized, this could leave more than half-a-million people across the country without coverage.

The criteria is heavily based on the number of hurricanes and not their economic impact. Look to other years with similar buzzword descriptors to determine if its impact is included in your organization’s systematic risk.

The criteria is heavily based on the number of hurricanes and not their economic impact. Look to other years with similar buzzword descriptors to determine if its impact is included in your organization’s systematic risk.