If a bunch of kids can launch a satellite into space, why can’t you?

As reported by the Washington Post, seventh-graders at St. Thomas More Cathedral School in Arlington, Texas are the first grade school students to send a satellite into orbit. The CubeSat – built by the children – was launched into space and will begin beaming photos from 200 miles above the Earth’s surface to an antenna on the school’s library.

This learning experience is remarkable for the kids, but what does it mean for the future of commercial industries in space? While commercialization of space tourism and satellite technology is already happening, is this emerging risk something that industries can afford to overlook?

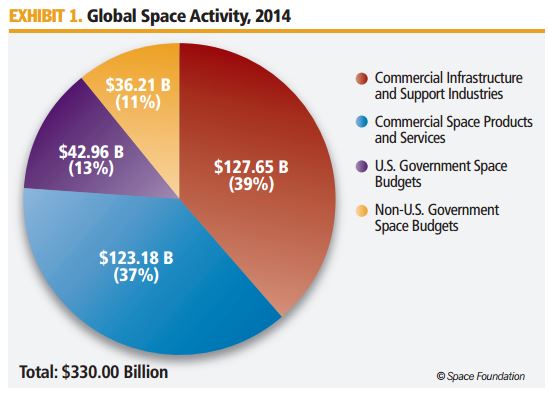

The Space Foundation’s 2015 “The Space Report” found that commercial activities in space continue to increase and now make up 76% of the global space economy. The report adds that revenue from commercial space products and services was dominated by direct-to-home television services, making up more than three-quarters of the global commercial space products and services market.

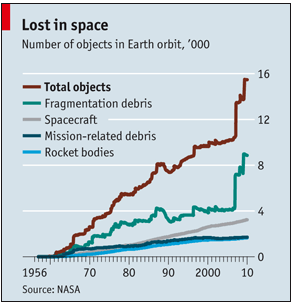

Allianz published an article that outlines some of the challenges of space insurance and space risks, from the pre-launch phases to in orbit operations and satellite insurance.

“Losing a spacecraft is by far not the only risk,” the article points out. “Potential interruptions of a satellite’s service in our globalized work are just as problematic for spacecraft users, individual transponders users such as TV channels and Internet providers, but also for banks, car manufacturers and large industries that use telecommunications networks.”

According to the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA / AST) Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2016, “The size of the global space industry, which combines satellite services and ground equipment, government space budgets, and global navigation satellite services (GNSS) equipment, is estimated to be about $324 billion. At $95 billion in revenues, or about 29%, satellite television represents the largest segment of activity.”

The report highlights the progress China has made with its space program, noting the number of orbital launches conducted by the country has steadily increased each year since 2010, with a peak of 19 launches in 2012. The findings highlight China’s commitment to commercial space applications, specifically stating that the data “points to a robust future in Chinese spaceflight.”

For many industries, the idea of planning for the risks involved in a space expansion might seem too far off to devote resources. But, with commercial airliners, telecommunications companies, international markets like China and even a bunch of seventh-graders already investing in opportunities in space, it might be time to reconsider the possibilities and the risks.