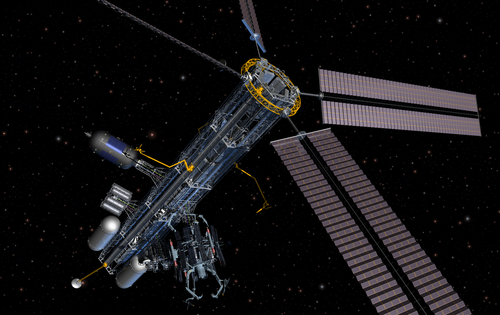

As captured – and tweeted – by skywatcher Bill Chater in the photo above, the European Space Agency’s Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE) re-entered the atmosphere on Sunday, making an uncontrolled fall after running out of fuel last month.

Launched in 2009, GOCE mapped variations in Earth’s gravitational field to help scientists better understand how gravity affects phenomena like ocean circulation and sea level. As Slate reported, the satellite only spent about a quarter of its time over land, so the odds were high for a safe crash into the ocean, but when an object weighing over a ton is in a free-fall to Earth, the risk is noteworthy.

While scientists knew that most of the satellite would burn up during approach, its 25 to 45 pieces of debris weighing up to 200 pounds each pose a significant threat. Without any means of controlling where it would land, officials from the ESA, Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee and United States Strategic Command closely monitored the massive “space debris” until it fell into the South Atlantic off the tip of South America, south of the Falkland Islands.

Since 2008, United Nations guidelines have attempted to reduce the danger of space debris, and scientists now build extra fuel and thrusters into space-bound objects to help control re-entry.

GOCE had already been designed when the guidelines were issued, but future iterations would likely include these failsafes.

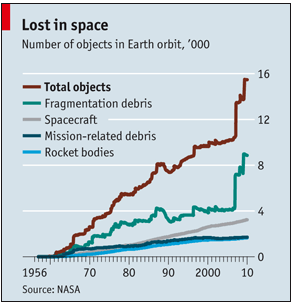

The risk of uncontrolled space debris is increasingly common, however. On average, one piece of tracked “space junk” falls every day and one intact defunct spacecraft or old rocket body comes back every week, BBC reported. Renowned astrophysicist Neil Degrasse Tyson was quite thorough in pointing out that major space debris disasters like the one depicted in Gravity are scientifically questionable at best, but the everyday risks merit serious consideration as increasing what we send into space increases what we can expect to fall back. There are currently about 750 live satellites circling Earth and an estimated 500,000 pieces of space debris in orbit, dating as far back as the 1958 Vanguard 1 research satellite.