Added capacity of pipelines used to transport crude oil and declining prices are contributing to decreasing transport of crude oil—and an almost 97% drop in the use of older, less safe transport cars between 2014 and the end of March, Gannett reported this week.

Rail tank car shipments of crude oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota have declined from a peak of 498,271 in 2014 to 424,996 in 2015, according to the Association of American Railroads. An AAR official made the announcement at a rail tanker car safety forum sponsored by the National Transportation Safety Board, according to Gannett.

In the December 2013 report “Moving Crude Oil by Rail,” the AAR noted that the rail industry has been urging federal regulators “to toughen existing standards for new tank cars” and recommended that the estimated 92,000 existing tank cars used to transport flammable liquids, including crude oil, be retrofitted with advanced safety-enhancing technologies, or phased out if they cannot be upgraded.

While there are obvious issues with the transportation of oil by rail, the AAR has pointed out that railroads have an excellent safety record with crude, even surpassing pipelines in recent years. But the industry and federal regulators acknowledge there is much room for improvement.

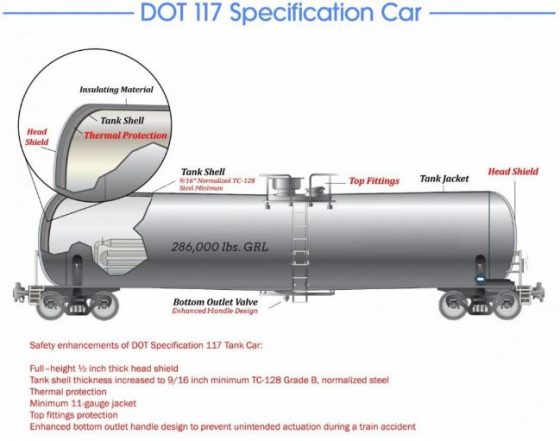

The new, safer tank cars have thicker steel shells, insulating materials, full-size metal shields at each end and improved outlet valves underneath the car. Increased use of the new cars is good news for densely populated areas on the east and west coasts that have numerous trains—often of at least 100 tank cars—moving through daily.

A transportation law, the FAST Act, signed by President Obama in December 2015, includes new mandates for freight trains transporting crude oil through the U.S. The law requires that older tank cars be replaced by the newer, safer car for shipping flammable liquids by March 1, 2018, phasing out the older model used, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

A rail disaster in Lac-Mégantic, Canada, on July 26, 2013, that killed 42 people brought a heightened focus on the dangers of transporting highly flammable Bakken crude oil by train.

According to the DOT, the rule also:

- Requires an enhanced tank car standard and an aggressive, risk-based retrofitting schedule for older tank cars carrying crude oil and ethanol.

- Requires a new braking standard for certain trains that will offer a higher level of safety by potentially reducing the severity of an accident.

- Designates new operational protocols for trains transporting large volumes of flammable liquids, such as routing requirements, speed restrictions, and information for local government agencies.

buy lariam online meadowcrestdental.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/jpg/lariam.html no prescription pharmacy

- Provides new sampling and testing requirements to improve classification of energy products placed into transport.

Last month, we focused on Mexico and specifically the state-owned oil company Pemex as a risk for companies selling or investing into Latin America. We saw that Pemex represents a drag on Mexican fiscal accounts and is imposing losses on suppliers and investors. This month, we turn our gaze to Brazil: it is similar to Mexico in that it has a dominant, politically charged state-owned oil company, but different because the scale of the crisis is much more severe, as are the risks to suppliers and investors.

Last month, we focused on Mexico and specifically the state-owned oil company Pemex as a risk for companies selling or investing into Latin America. We saw that Pemex represents a drag on Mexican fiscal accounts and is imposing losses on suppliers and investors. This month, we turn our gaze to Brazil: it is similar to Mexico in that it has a dominant, politically charged state-owned oil company, but different because the scale of the crisis is much more severe, as are the risks to suppliers and investors.